When I went to the Toronto Outdoor Art Fair, one of the booths I stopped at (but didn’t happen to mention on Substack) was a booth by StART Toronto, an organization that helps develop and promote the city’s street art and the artists that create it.

Part of the reason why I didn’t mention it was that the booth was so popular, I didn’t get much of a chance to take a close look.

But the organization’s name stuck in my head, and after I got home I looked them up online. On their website, there’s a map of street art locations – and I noticed that Queen Street was popular, particularly a place called Graffiti Alley, which I’d never been to before.

I’ve walked down the street so many times before, but when I took a walk with the intention of looking at the street art and graffiti around me, a different city emerged.

The first thing that struck me was this character painted in an alley:

To me, the bird was vaguely recognizable (although I can’t pinpoint where it’s from), and I liked the striking contrast between the pink and blue of the lettering. Drawing from hip hop and pop culture, street art is part of the legacy of graffiti artists, many of whom were Black and Latino artists like Basquiat and low-income artists who wanted to disrupt the white, moneyed status quo that gatekeeps and commodifies art.

Reading about street art when I got home reminded me that it’s (arguably) ontologically different from other types of art in a lot of ways: it’s ephemeral, often anonymous, often site-specific, and it’s free. Unless it has been commissioned, it’s not meant to be owned by any one person or organization – which raises issues when building owners try to dislocate and sell works by famous street artists.

In that way, a lot of street art resists the economic imperatives that shape so much of the city landscape. But the story there is complex.

I thought, intuitively, that “street art” was an umbrella term that encompasses graffiti – but apparently there’s a distinction, with a lot of overlap and controversy about where the boundaries lie.

The term “graffiti” seems to generally point to text-based and often illegal art forms created without seeking consent from the owner of the structure they’re painted on, often taking a stand against outsiders trying to dictate what it should look like. According to Straat Museum, graffiti also primarily speaks to members of the graffiti scene and is largely indecipherable to outsiders.

Alternately, street art is made to be more accessible, speaking to broad political issues or decorating a public space. Street art is also more often painted with permission, so there’s not the same risk and time-sensitivity involved in creating it.

As such, there’s some tension between street artists and graffiti artists. Some see street art as the “gentrification of graffiti,” especially since street art is inspired by graffiti art, yet also tends to deter graffiti artists from tagging over it out of respect, occupying spaces that might otherwise be ideal for graffiti.

The relationship is complex since street artists might be graffiti artists that worked their way into mainstream street art, or they might be artists with formal training that draw inspiration from graffiti. The latter group have never taken the risk involved in doing illegal work, but benefit from its legacy.

On Queen Street, there are a few signs that have clearly been commissioned, inspired by the presence of street art and graffiti in the area:

Is it a homage, or appropriation? I’m not sure.

But there is also street art that brings awareness to important social issues and supports underrepresented artists, such as Toronto’s Paint the City Black project in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020.

Along the same lines, one of the more striking murals on Queen Street was this one, commissioned by TD Bank in support of Black Designers of Canada:

In short, there are a lot of social and political threads to untangle when talking about street art and graffiti, and their interrelationship.

On the opposite wall was another mural that caught my eye. Its focal point, the rearview mirror, evoked the shiny chrome of the vehicle and rearview mirror in what seemed like only a few strokes.

When I turned down the alley to look closer, I saw that there was an entire row of garage doors that had been painted and painted over. Walking through, it seemed to be a mix of graffiti and street art that spoke to the tension and confluence of both.

Apparently this was the site of a laneway project first conceived in 2012, when artists were commissioned to paint murals on homeowner residences to deter what BlogTO calls “vandalistic tags.”

But in 2019, when a new artist was commissioned to paint 7 new murals, he painted over 26 murals instead, creating a scandal by covering up a lot of beloved artwork with black paint and a stenciled letter. Street artists have painted over the stenciled letters since then, but a lot of the black background paint remains, and it looks like a lot of graffiti has accumulated in the margins.

I like the way that these two art forms collide here.

The door on the upper left, in particular, looks like the portal to a different version of Narnia. Also I liked the character that looks like a doughnut with unfocused eyes and a moustache, and the characters with long noses peeking out from behind the blue background.

There were also a few works by graffiti artists who left their signatures. This “Peanut Butter” lettering by Durothethird caught my eye, and I found out later that he’s also the artist behind the So Beer mural on Queen Street. Apparently he worked his way into mainstream commissions after doing graffiti art for four years, and now focuses on custom BMX bikes.

I couldn’t help but notice that someone spray-painted the word “WOLF” in white letters to make the garage read, “Peanut Butter WOLF.” The first mental association I formed was of a rejected Twilight character, but it turns out that “Peanut Butter Wolf” is actually a DJ from LA.

Another mural by an artist with a clear signature was this one by Peru143, which reminded me of an abstract landscape. I like the subtle glittering effect that the white paint gives along the bottom of the piece to suggest a transition from a matte blue outline to a metallic one.

I also stopped to look at this one because the eyes of the characters were piercing. At first glance they looked like three-dimensional orbs popping out of the garage surface until my eyes adjusted. Apparently Birdo is a Toronto street artist known for his strange creatures.

Walking away from Ossington Laneway and back out onto Queen Street, I encountered another mural that I’ve noticed a few times before, commissioned for Sanko Trading Company in Toronto, a Japanese food store:

What strikes me is how these public murals turn these storefronts into instant landmarks. I might not have noticed The Roasted Nut or Sanko Trading Company as I walked by, but the artwork makes them stand out against the stores with more conventional branding that line the streets.

I can’t help but think of how beautiful the city would be with more paid commissions for artists like this.

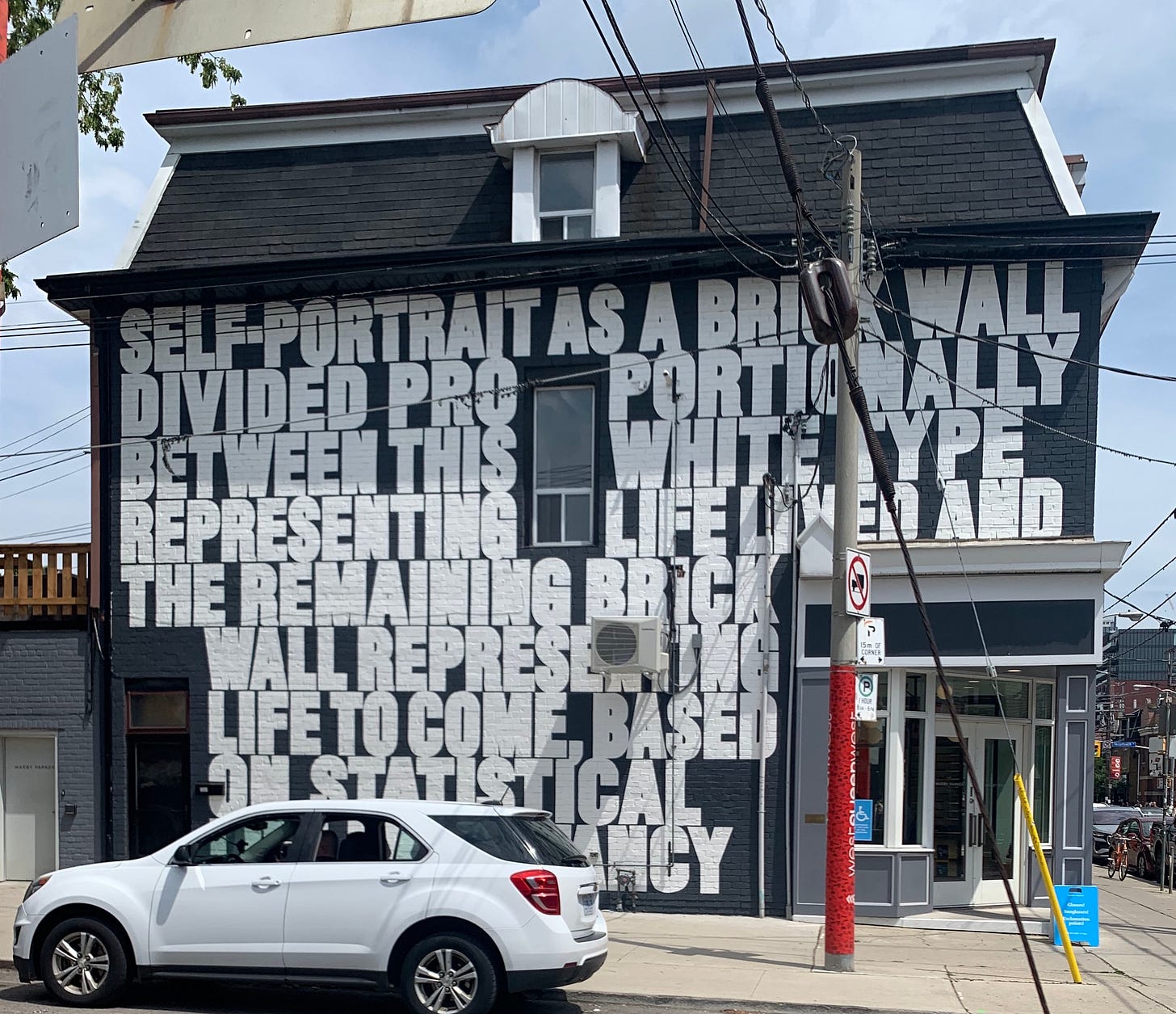

Some of the art also highlights the elements of the buildings themselves in a fun way. This work I came across is by Micah Lexier, whose work explores the interplay between text and architectural design. It highlights the strange lone window that peeks out of the otherwise solid wall by also having it interrupt his sentence.

There is a car in the way of the text at the very bottom, but the whole thing reads:

SELF-PORTRAIT AS A BRICK WALL DIVIDED PROPORTIONALLY BETWEEN THIS WHITE TYPE REPRESENTING LIFE LIVED AND THE REMAINING BRICK WALL REPRESENTING LIFE TO COME, BASED ON STATISTICAL LIFE EXPECTANCY.

It’s a variation on a 1998/2013 exhibition in which he created black text on a white wall with the same goal: to create a self-portrait as a statistic of how much longer he has left to live based on the ratio of black/white on the wall.

Since he’s a contemporary artist in a more traditional sense, I wonder if this represents the recent merging of contemporary and street art, or if graffiti artists would see it as encroaching on the space.

I like its presence though.

I made it to Graffiti Alley, which is apparently the only place in Toronto where artists can legally do graffiti.

A few of my favourite pieces were a purple rendering of Michelangelo’s David and another one of Laocoön, by an artist who seems to go by the name Bunso. I especially liked the interplay between the painting of David and the monkey either rolling its eyes or looking up at its exposed brain.

The next thing that struck me was this mural which is (I think) by Bruno Smoky, although it used to look quite different so I’m not sure if he changed it and left his original signature or if someone else painted over it.

To me, it looks like a movie poster for some sort of alternate version of The Neverending Story with a hair metal soundtrack and a giant blue pig instead of a flying dog.

I also liked this black and white piece which covered two floors of a loading garage, especially the detail of a realistic raccoon eating (being fed?) what appears to be a cartoon doughnut.

This one is also a reminder of how physically demanding a lot of street and graffiti art must be – I wonder what kind of scaffolding they used to help them paint the ceiling.

Finally, this piece by Uber5000 was an impressive mural that transformed a whole building into a wimmelbilder-style seascape with very expressive fish. My favourites are the ones on the right playing poker with a crab.

This whole tour has left me thinking: I wonder what Toronto would look like if street art were legal? It was made legal in Rio in 2009, was long as the artist is painting on a non-historic civic structure or has permission from the owner. Since then, Rio has become home to the largest street art mural in the world and many prolific artists.

I imagine that this kind of broad legalization would take away the time constraints that limit graffiti artists in places like Toronto, creating more opportunity for these artists to hone their skills and paint in daylight.